Sugar: the sweet little liar we’ve loved since childhood. It’s the star of birthdays, heartbreak cures, and festrival binges—yet behind every mithai, cupcake or a candy lurks a history sticky with slavery, greed, and global addiction. Before ‘kuch meetha ho jaye’ are you ready for its darkest secret?

We don’t actually need sugar. Our bodies get all the glucose they require from the humble carbs in rice, grains, and vegetables. But somewhere along the way, sugar transformed from a rare spice or medicine into a daily craving. It crept into our tea, coffee, chocolate, bread, sauces, and—let’s be honest—almost everything that makes supermarket shelves gleam with temptation. What started as a treat became an expectation, and before we knew it, humanity was hooked. And like all dangerous relationships, the affair came with baggage—this one involving slavery, empire-building, and entire economies addicted to sweetness.

The story begins, fittingly, with myths. Ancient Persians believed sugar was a literal gift from the gods. Zoroastrian legend credits King Jamshed with discovering a stalk dripping sweet juice, boiling it down into crystals, and presenting humanity with a divine symbol of light conquering darkness. Lovely origin story, but let’s just say what followed was less about divine gifts and more about divine greed. Sugar became central to ‘Navroz’ Persian New Year sweets, then spread with the Arabs as they expanded their empire. They brought not only Islam and trade but also a taste for desserts—introducing confections, syrups, and even the earliest version of “dessert as the meal’s finale.” What began as sacred became luxury, then habit.

China also caught the bug. By the Tang Dynasty, Chinese monks returning from India introduced sugarcane, and before long, skilled refiners in Fujian and Guangdong were producing crystals astonishingly close to what we spoon into our coffee today. Sugar became a status symbol—literally sculpted into statues for the wealthy. In short, sugar had leapt from temple medicine to table seasoning to full-blown lifestyle. Humanity was hooked, but there was one big problem: making sugar was hellishly hard work.

Enter Portuguese, troubled by venetian high price monopoly looked to follow the arabian model of – simply grow it elsewhere. Here comes Madeira Island in the 15th century, a lush Atlantic island turned into the world’s first industrial sugar colony. It was marketed as progress, but really it was the start of a nightmare. The Portuguese ran out of local prisoners for labour and began raiding Africa, dragging in Berbers first, then thousands more. Slaves hacked cane, dug irrigation canals, and fed boiling kettles day and night. Madeira soon had more waterways than Venice, but also a scorched landscape stripped of trees and exhausted workers with no choice but death or drudgery. This wasn’t farming—it was the template for global exploitation.

Economists call Madeira experiment as a turning point in human history. Before this colony, people moved according to basic human needs—safety, fertile land, access to food—and traded whatever they happened to grow or gather. Madeira flipped the calculation. For the first time, people moved because of commodities. Profit, not survival, became the driver. It was a radical shift: money first, subsistence later.

From a financial perspective, the Madeira experiment was dazzlingly successful. The profits it generated convinced investors and rulers that this model—plantation monoculture powered by coerced labour—was worth repeating. And repeat it they did. Among those who took notes was Bartolomeu Perestrelo, Madeira’s colonial leader, and his Genoese son-in-law: a young sugar trader by the name of Christopher Columbus. When Columbus stumbled upon the Caribbean, he saw not just “new worlds” but new sugar fields. Soon plantations blanketed the Americas, and slavery became turbo-charged. Millions of Africans were shipped across the Atlantic in chains—12.5 million in total, 70% of them forced into sugar. Average life expectancy on a Caribbean sugar plantation? Eight years. That’s right—slaves weren’t seen as workers so much as disposable machinery, to be replaced once broken.

And here lies the paradox: the cheap sugar that made European tea palatable, that sweetened chocolate, that created pastries, cakes, and candies for the masses, was purchased with human lives. Columbus ushering in the so-called Age of Exploration. In reality, it was an age of extraction.

Sugar Without Chains? Not Quite.

By the mid-18th century, Europe’s sweet tooth was insatiable. The plantations of the Caribbean were churning out mountains of sugar at the cost of African lives, but a quiet revolution was already underway in the East. While the Atlantic was a theatre of chains, ships, and blood, the Pacific offered something different: migration, machinery, and a veneer of respectability.

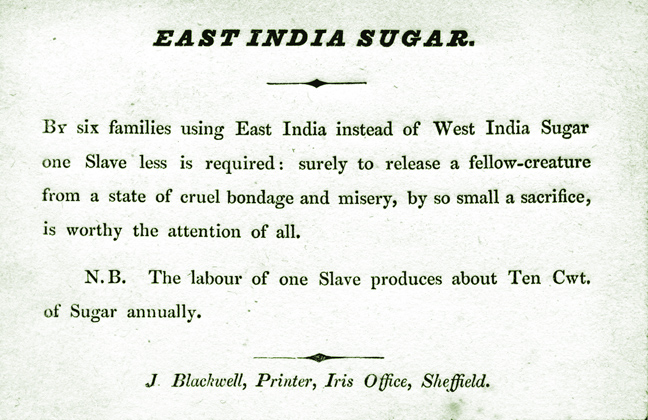

The Zong massacre in 1781 was as horrifying as it was absurd: a captain miscalculated rations, tossed 130 enslaved Africans into the sea, and then filed an insurance claim as “lost cargo”. Normally, such cruelty wouldn’t have made the news, but a freed slave Olaudah Equiano and lawer Granville Sharp turned it into a rallying cry. Suddenly sugar had a PR crisis. Half a million Britons swore off Caribbean sugar and demanded “Free Grown” imports from India instead—the world’s first consumer boycott. Bakeries proudly hung signs promising “sugar without chains,” and shoppers patted themselves on the back. Of course, the workers in India weren’t exactly sipping chai breaks between shifts, but hey, branding is everything.

The Dutch, always with an eye for profit, knew Brazil might slip through their fingers. So they turned to an island the Portuguese had nicknamed Formosa—“beautiful”—but which we know as Taiwan. Hardly empty but relatively underpopulated, Taiwan was a perfect blank canvas for the world’s most ambitious sugar scheme. Rather than drag enslaved Africans across oceans, the Dutch went shopping in Fujian. They recruited tens of thousands of disaffected Chinese farmers—the very descendants of the sugar masters who’d first refined crystals centuries earlier. By 1750, Taiwan wasn’t just dabbling in sweetness; it was the world’s leading sugar exporter, pumping out six times Brazil’s refined production. The Chinese even had a saying about it: “One cannot walk in Taiwan because money lies everywhere.”

The sweet stuff hadn’t grown moral—it had simply grown global.

Enter the Beet

Then Napoleon got involved. Cut off from Caribbean sugar by British blockades, he needed a homegrown fix. In 1811, French scientists pitched him an alternative: Beta vulgaris, the common beet. Thanks to decades of German tinkering, the beet’s sugar content had jumped from 1% to a respectable 20%. Napoleon ordered 70,000 acres planted, and voilà—Europe had its own domestic sugar source.

At first glance, this was progress: no chains, no equatorial death fields. Just beets. Harmless root vegetables boiled into crystals. But the real magic of beet sugar wasn’t humanitarian—it was industrial. By 1840, beets supplied 5% of the world’s sugar; by 1880, half. Beet sugar created monopolies, price collusion, and the very business models later copied by Big Oil.

It also turned sugar into a mass-market staple. Cookies, sodas, breakfast cereals—these weren’t luxuries anymore but everyday temptations, especially for children. By 1900, Americans went from eating 8 kilos of sugar per person to 41, most of it courtesy of brightly wrapped candies hawked to schoolkids. Sweetness was no longer elite—it was addictive, democratised, and branded.

Hitler’s Sweet Tooth and a Bitter Byproduct

But sugar’s industrial empire wasn’t finished making history ugly. The Nazis, cut off from foreign imports, doubled down on beet production. Hitler himself was a sugar junkie, downing two pounds of candy a day, with rotting teeth to prove it. More chilling, though, was beet sugar’s dirty byproduct: hydrogen cyanide. Refined into Zyklon B, it became the gas of extermination in Nazi concentration camps. Yes, the same beets that sweetened childhood candy also fuelled industrialised death.

Big Sugar, Big Lies

Even after wars ended, sugar never loosened its grip. By the 1950s, rising obesity and heart disease were being blamed on sugar. Enter the Sugar Research Foundation, a cheerful-sounding group with very dark habits. They paid Harvard scientists to “prove” fat—not sugar—was the true dietary villain. The result? Grocery shelves groaning with “low-fat” products stuffed with more sugar than ever. Consumption skyrocketed another 30%.

And as production scaled, so did the environmental footprint. Today, 8% of the Earth’s land is planted with cane, another 2% with beets. Most U.S. beets are genetically engineered to resist Monsanto’s Roundup pesticide—now owned by Bayer, the pharmaceutical giant that also sells the medicine for diseases linked to poor diet. That’s right: the same conglomerate profits when you eat sugar, when you get sick from it, and when you need treatment to keep going. Sweet deal—for them. Now here is a perfect case study in how sugar has become both product and parasite: feed people, sicken them, medicate them, repeat.

Sweet Tooth, Sick World

If sugar’s history reads like a morality play, the final act is still unfolding—and it’s playing out in our own kitchens, supermarkets, and hospitals. We’ve swapped slave ships for supply chains, cane fields for candy aisles, and imperial monopolies for multinational food conglomerates, but the plot hasn’t changed. Sugar remains our most profitable poison, cleverly disguised as happiness.

Its amazing how in less than three centuries, sugar – something we didn’t need biologically – went from being a rare medicine / delicacy to the invisible backbone of modern diets. We’ve quietly enslaved ourselves to cravings engineered in labs and polished by advertising.

An explosion of diabetes, obesity, heart disease, and liver conditions that cost health systems trillions annually. Ironically, these “modern epidemics” are just the latest fallout from sugar’s centuries-long march. Yesterday’s plantation masters squeezed profit from bodies in the cane fields; today’s corporations squeeze it from hospital beds. And that’s not even including the environmental price tag.

The irony is hard to miss. Sugar gave us capitalism’s first boycotts, its first monopolies, even its first global propaganda campaigns. It fuelled revolutions, financed empires, and—through beets—provided the Nazis with both candy and cyanide. And yet here we are, still spooning it into our tea, still handing it out at Halloween, still calling our loved ones “sweetie.” The same substance that built fortunes and empires is quietly dismantling our health and our planet.

So what’s the lesson? Maybe it’s that the “sweetest thing” has always come with the bitterest aftertaste. Its story is not about sweetness at all but about how easily pleasure blinds us to exploitation.

So pour yourself a drink, stir in a spoonful, and think about it. Every crystal of sugar is a tiny piece of history—sweet on the tongue, bitter in the legacy.

Leave a comment