If history had a guilty pleasure, it wouldn’t be wine, coffee, or even chocolate. It would be sugar. Those innocent little crystals have toppled diets, bankrolled empires, ruined teeth, and—quite literally—sparked revolutions. Today you can pick up a kilo at Tesco or the corner dukaan, but sugar’s journey from sticky cane fields to your chai glass was anything but simple.

This is the story of sugar: half dessert, half empire fuel, and—for a while—the Wi-Fi of the 18th century.

Sweet Beginnings: India’s Cane Fields

Long before Europe went weak at the knees for sugar-dusted cakes, India was already buzzing with the sweet stuff. Sugarcane grew like a jungle, and curious locals figured out that if you squeezed it, boiled it, and stirred it long enough, you got jaggery (that rustic brown stuff) or, even better—shiny golden crystals. Sanskrit gave us the word śarkarā. This morphed into sucre in Europe and sugar in English, before circling back to India to replace the original word.

Meanwhile, Egyptians decided sugar should sparkle. They made crystallised blocks and, as they supplied it back to India, it came to be called misri (from Egypt). Even today, in India and Pakistan, people still pop a chunk of misri with fennel seeds after a heavy meal.

China wasn’t about to be left behind. They refined sugar so white and crystalline it looked like jewels. Indians were so impressed they literally named sugar after China—chini. That’s linguistic fan mail, 9th-century edition.

And then there’s khaṇḍa (from the khandasari communities who made cane sugar). This little word hitched a ride with Arab traders, travelled the Silk Route, and popped up in city names like Samarkand and Tashkand. Later, when hard-boiled sweets landed in Victorian Britain, they sailed back to India as “candy”— completing a full circle of linguistic and culinary exchange.

But then, what’s in a name?

The Arab Sweet Tooth

If India was sugar’s birthplace, the Arabs were its greatest early ambassadors. From the 7th century onwards, Islamic empires spread both sugarcane cultivation and new techniques of refining. The Arabs established sugar plantations in Persia, North Africa, and eventually in southern Spain and Sicily. Sugar became a prized ingredient in the Islamic Golden Age—used in medicines, syrups, and elaborate confections shaped into flowers, animals, and miniature palaces. These edible sculptures inspired European travellers who returned home with tales of the “sweet salt.”

By the time Crusaders returned to Europe in the 12th century, sugar was firmly on their wish list. But supplies were limited and prices sky-high. For centuries, Europeans treated sugar less as food and more as a rare spice, to be used sparingly alongside cinnamon, nutmeg, or pepper.

For medieval Europe, sugar was medicine. Physicians prescribed it to balance bodily humours, soothe coughs, and preserve fruit. By the Renaissance, however, sugar had crept into the dining hall, where it became a display of status. Sugar, literally, was a showpiece.

Venice became an early hub for refining, but it could not keep up with the cravings of Europe’s wealthy.

Soon, the search for new sources would change the world.

Plantation Economics: Sweetness with Chains

No history of sugar is complete without Sidney Mintz, the anthropologist who wrote Sweetness and Power. Mintz showed how sugar wasn’t just a treat—it was a driving force in global economics, slavery, and diet. As Europe’s sweet tooth grew insatiable, Venice couldn’t keep up. Enter: the Americas. Cane fields were planted across the Caribbean and Brazil, and voilà—plantations. But the engine of this sugary machine wasn’t technology. It was people—enslaved Africans, millions of them, shipped across the Atlantic like human cargo.

Between the 16th and 19th centuries, about 12 million Africans were enslaved, and nearly half ended up in sugar colonies. The work was brutal: cane cutting under a blazing sun, hauling stalks to mills, boiling juice in furnaces hot enough to roast you alive. The average life expectancy of a slave in the Caribbean? Seven years. Plantation owners in Barbados openly admitted it was cheaper to “work slaves to death” and replace them than to feed them properly. Sugar profits trumped human life.

Saint-Domingue (modern Haiti) became the sugar capital of the world, supplying half of Europe’s cravings. But in 1791, the enslaved population revolted—and won. Haiti’s independence sent shockwaves across Europe.

Sugar wasn’t just food; it was revolution fuel.

The Triangular Trade: The World’s Stickiest Supply Chain

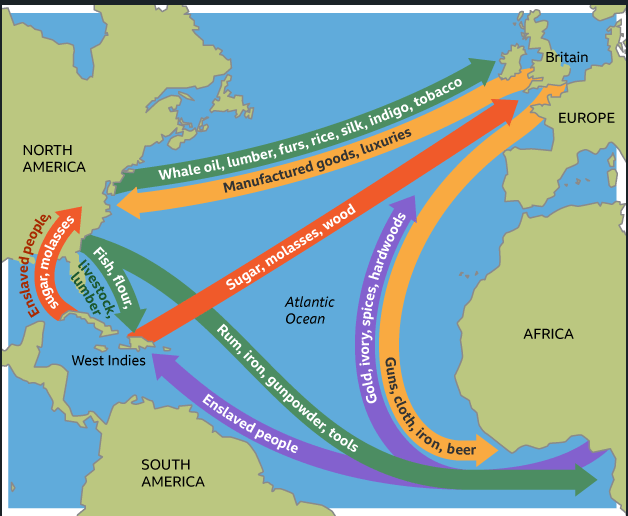

Sugar’s rise created a neat little system economists now call the “triangular trade”:

- Europe shipped textiles, guns, and trinkets to Africa.

- Africa sent enslaved people to the Americas.

- The Americas shipped back sugar, coffee, cocoa, and rum.

Rinse, repeat, profit.

By the 18th century, sugar wasn’t a luxury anymore. It sweetened tea, jam, and porridge, fuelling the Industrial Revolution. Workers guzzled sweet tea—without sugar, those 16-hour factory shifts might have been shorter. Children were hooked on candy. Merchants? They were rolling in sticky cash.

Beet It: Napoleon’s Sweet Hack

For centuries, cane ruled supreme. But then Napoleon got blockaded by the British. No Caribbean sugar? No problem. Enter: sugar beet.

Scientists extracted sugar from humble European beets and, voilà—local supply. Suddenly, sugar was no longer chained to tropical colonies. By the 19th century, beet sugar factories sprouted across Europe. Cane lost its monopoly.

Industrialisation did the rest. Steam engines, railways, and mechanised mills meant sugar production skyrocketed. By 1900, sugar was showing up everywhere: in biscuits, jams, chocolates, and fizzy drinks.

Basically, if you could chew it, drink it, or spread it on toast, sugar was in it.

Handle With Care

Sugar’s legacy didn’t end with empire. In the 20th and 21st centuries, it became entangled with new debates—not about slavery, but about health. In many ways, sugar remains what it has always been: addictive, profitable, and controversial.

From India’s cane fields to Egyptian misri, from Chinese white crystals to Caribbean plantations, sugar has been medicine, luxury, staple, and empire fuel. It has built fortunes and sparked revolutions. It has ruined teeth and toppled waistlines. It has been, at once, delight and devastation.

If history teaches us anything, it’s this: never underestimate a substance that can launch empires, ruin teeth, and sweeten chai—all in one spoonful.

Leave a comment