In the heart of every Gurudwara (Sikhism place of worship), amidst the echoes of sacred hymns and the aroma of spices, lies a profound tradition known as Langar. Langar is a free community kitchen service where everyone, regardless of their background, is welcome to share a meal together. However, Langar is not just a meal; it’s a symbol of unity, humility, and community service deeply rooted in the Sikh faith. This month, I had the privilege of partaking in this timeless tradition as a sewadaar, or volunteer, at my local Gurudwara in Tooting (London). The experience left a soothing experience highlighting the beauty of selfless service and the power of togetherness.

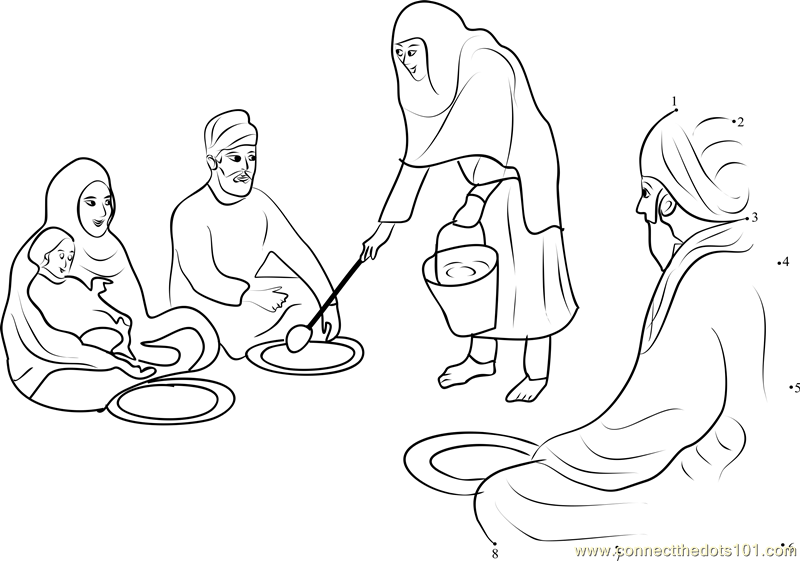

To truly appreciate the significance of Langar, one must delve into its historical roots. The tradition of Langar traces back to the founder of Sikhism, Guru Nanak Dev Ji, in the 15th century. At first glance, langar may seem like a community kitchen where the responsibility lies with the community to cook and serve food. However, langar had a profound objective—to foster unity and equality. It aimed to dismantle the caste system that had permeated Indian society, where social divisions dictated who could dine with whom. Langar aimed to break down these barriers, ensuring everyone sat together and shared meals, transcending societal differences.

Langar does not exist in a vacuum; one of the oldest Sikh sayings is ‘Degh, Tegh, Fateh‘ (‘The Cauldron, The Sword, Victory‘). Langar is the foundational Sikh revolutionary space. It’s a space to gather and engage in discussions about the ideas of the house of Guru Nanak. There are countless stories of how it has served as a sanctuary for oppressed, offering them an opportunity to dine with the Khalsa (sikh brotherhood) and learn about our ongoing struggle for justice and equality. Langar isn’t merely a passive setting for receiving a free meal; it’s about active participation and solidarity.

Even Emperor Akbar had to have the langar before meeting Guru Ram Das. The practice continues in Punjabi hospitality – eat first, discussion later is the affectionate manner in which most elders will welcome you in their homes even today….’Langar chakko’ (first taste the Langar food) is the priority. This tradition dates back to ancient times when villagers would contribute one-tenth of their harvest, known as ‘Dasvandh,’ to the Gurudwara as an offering to the divine. These diverse donations were then combined and cooked together, symbolizing unity and shared responsibility. The slogan “hello langar, goodbye world hunger” doesn’t capture its true essence. Langar has a rich history of bringing people together as equals and inspiring initiatives for the greater good.

Centuries later, the spirit of Langar continues to thrive within Sikh communities worldwide. Every day, dedicated volunteers, known as sewadaars, gather in Gurudwaras to prepare, serve, and clean up after the Langar meal. What makes Langar truly remarkable is its accessibility; it is open to everyone, regardless of faith, caste, or socioeconomic status.

My Journey as a Sewadaar:

Entering the bustling kitchen of the Gurudwara, I was enveloped in a symphony of clanging utensils and the rich aroma of spices. Alongside fellow sewadaars, I delved into the art of crafting nourishing meals for the community. But this was no ordinary kitchen duty—it was a labor of love, infused with devotion and purpose.

The enormity of the task loomed large, as this was the vibrant Vaisakhi celebration weekend, with a three-day Akhand path (continuous reading of the holy book) leading up to the auspicious day. Excitement buzzed in the air as we braced ourselves for the anticipated influx of guests for days, with the Gurudwara expecting a crowd of 150 to 200 people on Sunday morning alone. Our routine morphed into a relentless cycle of preparation, cooking, serving, and cleanup…and REPEAT; a rhythm that echoed throughout the bustling kitchen.

Preparations commenced days in advance, far beyond mere vegetable chopping. We tended to sacks of produce with care, ensuring that each ingredient received the attention it deserved. I quickly learnt that sautéing 25 kilograms of onions is a laborious eye watering task that demanded hours of continuous stirring and scraping. The cooking cauldrons, towering in size, required the use of four-foot-long ladles without spilling things around…a big strenuous upper arm workout of a few Gym sessions..and yet far more satisfying.

Once the base curry sauces reached perfection, they were carefully stored in massive pots, awaiting their transformation into special Langar dishes. While staples like daal and sabji (vegetable) grace every Langar spread, Vaisakhi called for special attention to the Punjabi sweet tooth, ensuring that every meal concluded on a sugary high—a testament to the adage, “kuch meetha ho jaye,” (lets have something sweet) where sweetness was as essential as any other element.

Imagine the patient art of reducing 30 liters of milk over a low flame, infusing small rice kernels with the creamy richness of milk and the fragrance of saffron. It was not merely a spoonful of sugar; it was kilos of sweet, sugary love poured into every batch. The gentle rhythmic stirring and inhaling of the fragrant spices for hours was almost a meditative experience.

Amidst the organized chaos, there was an unspoken camaraderie—a seamless coordination where everyone knew their role and anticipated each other’s needs. I often found myself receiving gentle nudges on ladle-holding techniques or a helping hand appearing out of nowhere to assist with moving large utensils. It was a surreal experience, where moments of chaos seamlessly merged with moments of serene cooperation.

As the hours melted away, I found myself immersed in the camaraderie of the kitchen, bonded by a shared purpose and a collective spirit. But the true magic unfolded during the langar meals themselves. Witnessing individuals from all walks of life, gathered in the pangat, or long rows, was an amazing sight. Strangers and friends shared in the warmth of communal meals and heartfelt conversations….an awesome gratifying experience!

LANGAR WALI DAL – A Hearty Dish Cooked with Love!

One of my aspirations from the experience was to learn the secret recipe behind that delicious langar wali dal. What I realized was that the essence of langar lies in communal cooking and eating, making it impossible to pin down a specific recipe. Langar is cooked from whatever people have donated and the offerings vary from flour, vegetables, lentils to rice. These diverse donations were then combined and cooked together, the composition and flavour may be somewhat different everytime with one common denominator – the love and dedication of the Sewadars which is the real secret to giving rise to the beloved ‘Langar wali dal.’ Therefore, there exists no fixed recipe for the dal served at langar, as it goes against the very principle of langar, which encourages the donation of whatever one can and the preparation of sacred food from these contributions.

But I did ask around the prominence of black gram in Punjabi cuisine is noteworthy. Why do Punjabis consume it in abundance? Interesting learnings to ponder…There were suggestions for reasons behind this culinary preference.

Firstly, from a scientific standpoint, the northern regions of India, including Punjab, predominantly consume rotis (flatbreads). Consequently, the dal recipes are often thick and viscous to complement the rotis, ensuring they can be easily scooped and enjoyed together. Black gram yields a wholesome viscous texture which makes it easier to eat with roti.

Secondly, the traditional use of tandoors in North Indian cooking plays a role. After using the tandoor for baking, residual heat was often utilized for slow-cooking dals, such as black gram, perfectly aligning with Punjabi culinary practices. This is also the reason of the slow cooked dals to have the buttery texture and viscousity of a makhani dal. Plants naturally produce a mucus-like substance composed of complex polysaccharides, which serves to store water and prevent the seed (or dal) from drying out during germination. This mucilage acts as a protective barrier, absorbing water and swelling to facilitate the breaking of the seed coat, allowing the baby plant to emerge. When whole black gram is soaked for extended periods and cooked over low heat for hours, this inherent mucilage contributes to the natural thickness and creaminess of the dish.

This phenomenon is the true essence of “Makhan” in a makhani dal—not the generous dollops of butter often added by restaurants. Unlike these shortcuts, the slow and deliberate cooking process in a Punjabi langar preparation allows ample time for the dal’s mucilage to infuse, resulting in a rich and velvety texture that epitomizes the authentic essence of the dish.

Leave a comment