Tea is never just a drink—it’s a passport, a rebel yell, a smuggler’s secret, a healer’s tonic, and a daily comforter. From its first simmer in the misty hills of China to its place on kitchen tables around the world, tea has travelled with monks, merchants, monarchs, and spies. Along the way, it’s been pressed into bricks, poured in palaces, disguised in pigtails, dumped in harbours, and planted on faraway hillsides. Every sip carries the memory of caravans crossing deserts, ships chasing monsoons, and empires rising and falling over a humble leaf.

Its story isn’t just about trade routes and treaties—it’s a saga of daring disguises, ruined crops, revolutions in teacups, and quiet rituals that shaped cultures. If tea could talk, every cup would whisper a tale: smoky, sweet, bitter, or bold. So let’s pour ourselves one, settle in, and follow tea’s epic voyage across centuries and continents.

From China to Its Neighbours

In its homeland, tea began as medicine. Monks in China believed it cleared the mind like a sudden mountain breeze, and poets swore its bitterness sharpened the tongue for verse. It was earthy, grassy, and just a little astringent—the kind of flavour that makes you sit straighter.

By the 12th century, Japanese monks returning from China carried home a handful of seeds. In monastery kitchens, bowls of green froth were whisked to keep eyes open through long nights of chanting. Eventually, this became the Japanese chanoyu, or tea ceremony. Imagine it: a tatami mat, a rough clay bowl warm in your hands, steam rising as you bow to your host in perfect silence. Tea wasn’t just drunk—it was staged, like a miniature play about patience, beauty, and grace.

🍵 Tasting Note – Matcha (Japan)

- Flavour: Grassy, umami-rich, slightly bitter

- Texture: Frothy, creamy, coats the tongue

- Feeling: Focused calm, like a monk at sunrise

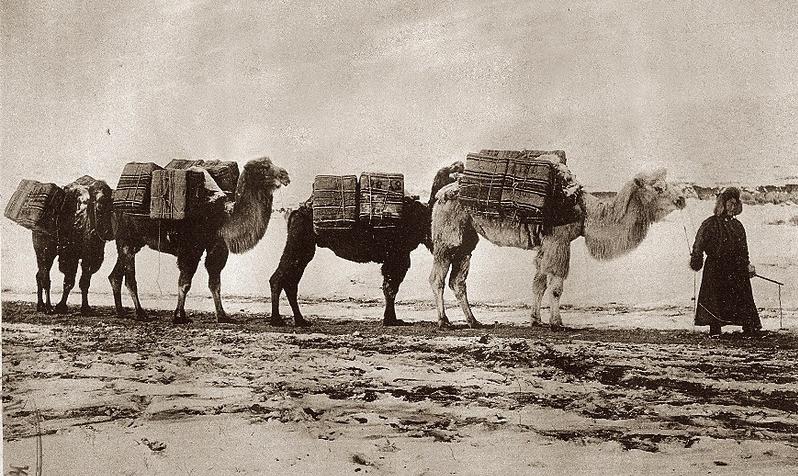

Russia’s Camel Caravans

When tea trekked north to Russia, it did so slowly—very slowly. Picture a caravan of camels plodding across the Gobi Desert, each laden with bricks of compressed tea wrapped in leather. These bricks were so tough that travellers sometimes shaved them into soup pots, flavouring broth with a hint of tannic bitterness.

By the time the bricks reached Moscow—after two or three years—they carried a smoky tang from the countless campfires where caravans had paused to rest. Russians fell in love with it. They drank it not plain, but sweet, with spoonfuls of jam melting into the hot liquid, turning it into something like liquid dessert. The samovar, that brass, bubbling urn, became the hearth of every home: warm, hissing, always ready to refill a glass with smoky, jam-sweetened comfort…and the samovar became the beating heart of every home.

🍵 Tasting Note – Russian Caravan Tea

- Flavour: Smoky, tarry, campfire-like

- Texture: Smooth, rounded by sugar or jam

- Feeling: Warming, like sitting by glowing embers

Portugal, England, and the Queen’s Teacup

Europe first sniffed tea through Portugal’s port in Macau. But the drink might have remained an exotic oddity if not for Catherine of Braganza. When the Portuguese princess married Charles II of England in 1662, she carried tea caddies with her as part of her luggage.

At first, courtiers gawked—this strange infusion was dark, bitter, and costly. But Catherine insisted, sipping it delicately with sweet preserves, marmalade, and even biscuits. Soon the fashion spread. Aristocrats imported fine porcelain from China—tiny cups so thin you could see the light through them—to sip their new status symbol.

It wasn’t long before the teapot became the centre of English drawing rooms, and tea the social glue of an empire. Catherine had done more than bring Bombay as dowry—she had unknowingly launched Britain’s most beloved ritual: afternoon tea..and within a generation, tea had turned into England’s favourite ritual.

🍵 Tasting Note – Early English Teas

- Flavour: Earthy Chinese black teas, mellowed with sugar

- Texture: Thin but fragrant

- Feeling: Elegant, like a velvet-gloved handshake

East India Company’s Liquid Gold (and its Shadow)

For the East India Company, tea became “liquid gold.” By the 18th century, fleets of East Indiamen ships sailed from Canton with their holds stuffed with crates of leaves. But China wanted only silver in return, draining Britain’s reserves.

The Company’s answer was a scandal: opium. They grew it in India, smuggled it into China, and traded it for tea. The silver stayed in Britain, while addiction spread through Chinese towns. Every English teacup in the 1700s carried, invisibly, the bitterness of this exchange. The fragrant steam on London’s streets masked the smoke of opium dens in Canton.

Every London teacup carried an invisible bitterness: the shadow of the opium trade.

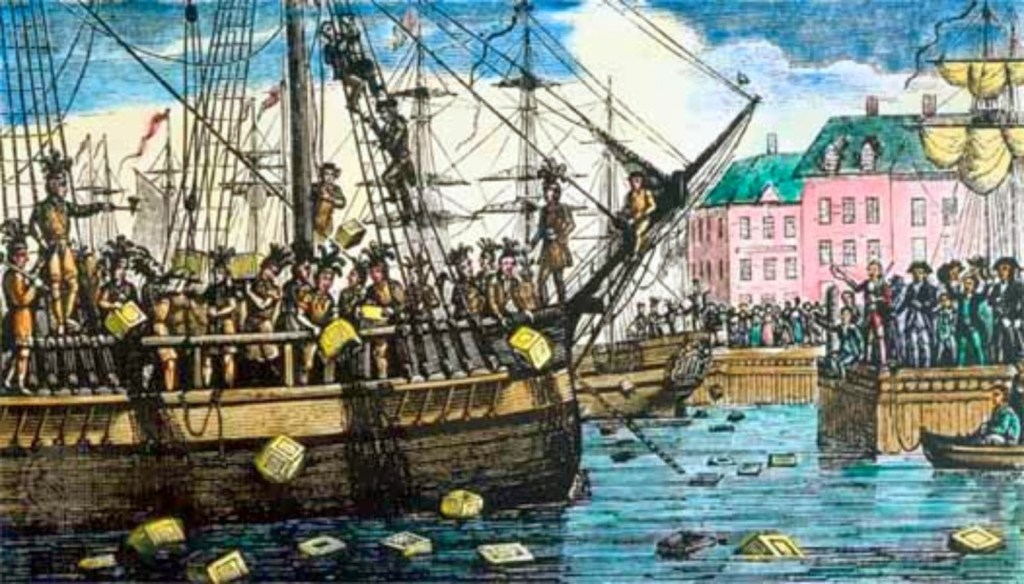

The Boston Tea Party: Revolution in a Teacup

Across the Atlantic, tea carried a very different story. In colonial America, it was already the daily drink. But taxes turned it bitter. When the Tea Act of 1773 gave the East India Company a monopoly, colonists fumed.

On December 16th, a group of men dressed as Mohawk warriors boarded three ships in Boston harbour. They split open 342 chests and tipped the leaves into the icy water. Imagine it: the smell of strong black tea rising from the sea, the harbour stained brown, fish swimming through what was essentially the world’s largest teapot.

The Boston Tea Party wasn’t about taste—it was about freedom. Yet, ironically, America never gave up the drink. By the 1800s, shipments resumed, and teapots clinked again on American tables, even as coffee rose as a rival.

The salty sea smelled like the world’s biggest teapot. America had turned tea into protest.

The Great Tea Heist

Even this wasn’t enough. In the 1840s, Britain sent botanist Robert Fortune on one of history’s strangest spy missions. Dressed in silk robes and wearing a shaved head with a pigtail, he posed as a Chinese merchant. Fortune sneaked into guarded tea gardens, copied secret processing methods, and smuggled out seedlings, seeds, and even workers.

In Darjeeling’s misty hills, those stolen plants flourished, producing light, floral teas so fine they were dubbed the “champagne of teas.

It was botany by espionage. Packed in Wardian glass cases, those stolen plants sailed to India, where they took root in Darjeeling’s misty slopes. If you sip Darjeeling today—light, floral, almost muscatel—you’re tasting the success of a Victorian plant thief in disguise.

🍵 Tasting Note – Darjeeling

- Flavour: Floral, muscatel grape-like

- Texture: Light, crisp

- Feeling: Refined, like sipping springtime from a porcelain cup

Assam: The Wild Leaf Tamed

While Fortune was sneaking through China, another story brewed closer to home. In Assam, locals had long been brewing a bitter, invigorating drink from wild bushes. These weren’t Chinese imports but a whole new species—Camellia sinensis assamica, taller and tougher than its delicate cousin.

At first, the Company dismissed it as unsuitable. But when planters tried cultivating it properly, they discovered its strength and richness made the perfect base for hearty blends. Soon, Assam tea plantations stretched across the Brahmaputra valley.

This once-wild leaf became the bold, malty backbone of “English Breakfast” tea—the very brew that fuelled the empire’s mornings.

🍵 Tasting Note – Assam

- Flavour: Malty, bold, coppery

- Texture: Full-bodied, almost chewy

- Feeling: Energetic, like a brass band waking you up at dawn

Ceylon: Coffee Falls, Tea Rises

In Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka), the story brewed from disaster. Coffee had been the island’s treasure—until the 1860s, when a rust fungus turned green coffee leaves into skeletons. Plantations collapsed almost overnight.

Desperate, the planters (many Scots again) gambled on tea. They planted rows across the rolling hills, where cool mists and rich soil worked their magic. To their surprise, the results were spectacular. Within a generation, “Ceylon tea” was famous—brisk, golden, and fragrant, the kind of tea that clears the palate like sunshine in a cup.

The island that had lost coffee gained a new identity: endless green hills of tea, climbing skyward like a carpet to the clouds. The island was reborn as endless waves of green, tea bushes rolling up to the clouds.

🍵 Tasting Note – Ceylon (Sri Lanka)

- Flavour: Brisk, citrusy, fresh

- Texture: Bright, clear

- Feeling: Uplifting, like a breeze through open windows

Africa: Tea’s Newest Home

In the 20th century, tea finally reached Africa. Kenya’s highlands, with red volcanic soil and cool nights, produced a punchy, bright tea that rivalled Assam. Rwanda followed, with mist-wrapped hills yielding fragrant, honeyed cups.

Today, African teas fill supermarket blends and premium tins alike, carrying the sunrise of the highlands into mugs worldwide.

🍵 Tasting Note – Kenya & Rwanda

- Flavour: Bright, brisk, sometimes honeyed

- Texture: Strong but clean

- Feeling: Invigorating, like a trumpet blast of sunshine

A Drink Steeped in Intrigue

From smoky tea bricks to stolen seedlings, from Boston’s salty harbour to Kenya’s volcanic slopes, tea has shaped empires, revolutions, and daily rituals.

So next time you sip—whether it’s malty Assam, floral Darjeeling, brisk Ceylon, or lively Kenyan—pause. You’re not just drinking leaves. You’re sipping centuries of stories, some sweet, some bitter, all unforgettable.

Leave a comment